Written by Dave Stevens

How did Precision Teaching get started? What research and researchers helped to shape it? This article is a great start to understanding what brought around Precision Teaching and how it was developed over the years. Our top takeaways are these:

- Six basic tenets from B.F Skinner’s experimental analysis of behavior

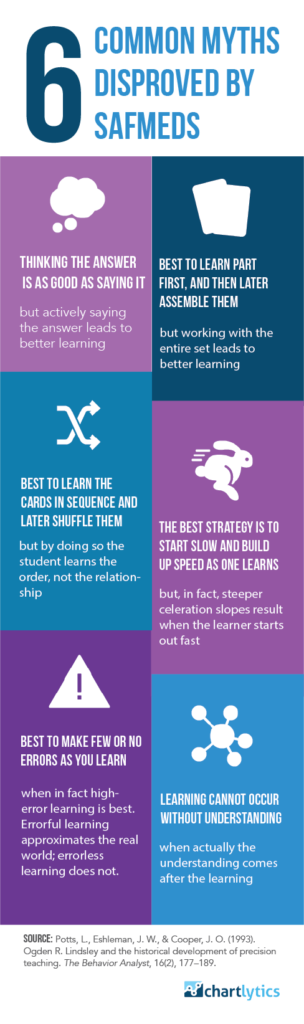

- Six (still!) common myths disproved by SAFMEDS

- Five reasons student self-charting is huge

Six basic tenets from Skinner

While Ogden Lindsley also pulled principles from Ivan P. Pavlov (1849-1936), Walter S. Hunter (1880-1954), Fred Keller (1899-?), he took at least six from B.F. Skinner.

“Precision teaching inherited six basic tenets from Skinner’s experimental analysis of behavior (Lindsley, 1972): (a) consequences control operant behavior; (b) “the learner knows best” (originally stated by Skinner as “the rat knows best,” signifying that organisms are simply responding according to whatever contingencies have been arranged); (c) work with observable behavior; (d) monitor frequency daily; (e) use frequency as a universal, standard, and absolute measure of behavior; and (f) adopt a standard display for data.”

Six common myths disproved by SAFMEDs

“As Lindsley (1983) noted, the use of SAFMEDS [Say All Fast Minute Each Day] dispelled some common myths about how we learn. Research with SAFMEDS generated a number of unexpected findings, which Lindsley characterizes as “counterintuitive.” These counterintuitive discoveries were induced, among other inductive discoveries, from a database consisting of 11,900 charts (Lindsley, 1993). Each word in the acronym SAFMEDS relates to a counterintuitive discovery.

- One myth is that “thinking the answer is as good as saying it,” but actively saying the answer leads to better learning.

- A second myth is that it is “best to learn part first (e.g., 10 cards), and then later assemble them,” but working with the entire set leads to better learning.

- A third myth is that it is “best to learn the cards in sequence and then later shuffle them,” but by doing so the student learns the order, not the relationship.

- A fourth myth is that “the best strategy is to start slow and build up speed as one learns,” but, in fact, steeper celeration slopes result when the learner starts out fast. Going fast from the start is counterintuitive, especially because the learner is unlikely to know the relationship between text and response. Would not many errors result?

- A fifth myth is that it is “best to make few or no errors as you learn,” when in fact high-error learning is best. Errorful learning approximates the real world; errorless learning does not.

- A sixth myth is that “learning cannot occur without understanding,” when actually the understanding comes after the learning.

These myths were disproven by SAFMEDS, which means that the concept relates not only to a procedure for doing flashcards, but also has more far-reaching implications.”

Five reasons student self-charting is huge

“From the beginning of precision teaching, Lindsley insisted that learners self-count and self-chart their performances. Clearly by 1968, precision teachers established that most learners, even first-grade students, can self-count, chart, and make instructional decisions based on charted data (Bates & Bates, 1971; Lindsley, 1990). Self-charting is cost-effective and reliable, produces better learning than a teacher-charted system, creates trust between the student and teacher, and gives learner ownership of the data.”

Bonus: Why is the Standard Celeration Chart blue?

Lindsley’s SCC research team found that “‘Most charters preferred a shade of green. The light blue chart, however, produced the highest accuracy of charting and was more resistant to fatigue than green. The chart has appeared in light blue ever since this evaluation’ (Lindsley, 1991b).”

References