This is the first part of a 2-part blog addressing the importance of instructional design. The first part sets the stage of why instructional design is important. The second part addresses how it is used in ABA and benefits from incorporating it.

Why Should We Care?

Instructional Design is an integral part of the role of a behavior analyst. Whether you are a professor, an organizational consultant, a supervisor of neurodivergent clients, working in the schools or academics, it shows up. It is in nearly everything we need to do in almost all roles we could serve. Instructional design can aid in forming quality undergraduate/graduate classes. It can lead to a robust training for a sales team. Instructional design is the first step in respecting your learner because you are setting them up for success before providing intervention.

Yet, training in instructional design is lacking or at best executed fast and loose. Sparingly, graduate programs address instructional design formally; however, most behavior analysts come into contact with ‘curriculum design’ or ‘program generation’ via supervisory experience. So, some behavior analysts practice pieces of design, but not scientifically, or precisely. And it becomes accessible enough and our learners progress enough that we don’t question the design.

I attended the Illinois Applied Behavior Analysis conference in February of 2020. One of the invited speakers, Dr. Rachel Taylor, mentioned the frightful Tricare study (Department of Defense, 2019). The authors of the study concluded that ABA did not produce any meaningful results. While the study has concerns that have been voiced by other behavior analysts, Dr. Taylor said, “What about the programming? How do we know the clients received quality programming?” (Taylor, 2020). Yes. Exactly. Hold on to this point - we’ll come back to it.

Quality Instructional Design Within A Curriculum

As we observe skills develop, we see how they explode, multiply. As young, early learners, we start with having a few skills. We hold our heads up, we roll over, we can turn our heads and look at things. Eventually, we start to stand alone, walk, point, mand (possibly via different modalities), feed ourselves to some extent, push, pull, laugh, follow some simple directions, respond in some manner (smile, attempt to sing, dance) to familiar songs, shows, people, toys, etc. We then start to pretend, share, engage in behaviors that suggest a notion of ‘ownership’, match and sort, tact, run, jump, climb, explore, catch, draw (without precision), attempt to be independent with some routines (e.g., brushing hair, brushing teeth, dressing), play for an extended period of time in a singular location, etc. As skills develop across a learner, it starts with just a few skills. Yet, as the learner develops and learns new skills, each acquisition yields not to just 1 new acquisition, but multiple skill acquisitions. And these new skills are skills that are across ‘domains’ or ‘content’ areas. We see skills in motor, language, social, adaptive, play, etc. emerge as the skills develop over time. It doesn’t grow as a long list of skills, it expands like a spider’s web.

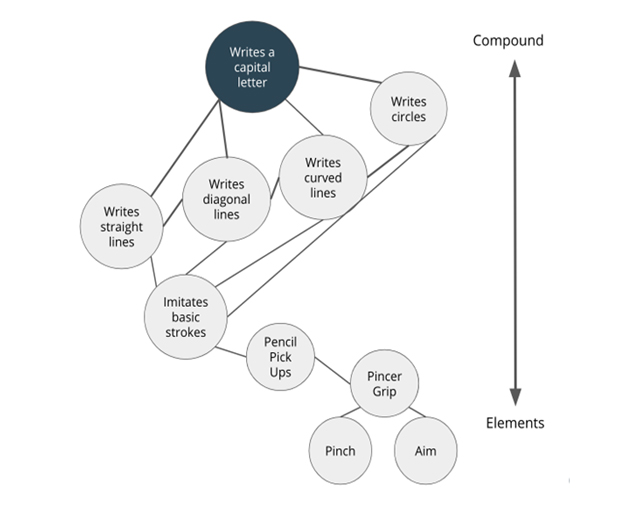

This web is demonstrated in an element-compound analysis.

In the figure above, the overarching compound (navy) is writes a capital letter with elements under it required to do this skill with accuracy and proficiency. However, we can see the element-compound relationship within the ‘gray’ skills as well. So while pincer grip is an element of writes a capital letter, it is also a compound that is made up of pinch and aim elements.

Yet curricula available to behavior analysts are not often designed in this manner. Many curricula present 2 scenarios: 1) there are no instructions on the progression of implementation or 2) the clinician is to implement programs linearly (sometimes within a content area, sometimes just linearly within the entire programming without regard to the content area). On one hand, these curricula do not want to be prescriptive - they yield the program discretion completely to the behavior analyst working with the client, which is as it should be. No one understands the variables and learning history of that client more than the behavior analyst working with the client. However, it also assumes that the behavior analyst has not only the experience but also the time to conduct element-compound analyses and create individualized programming for all of these programs.

Finally, a linear approach to curriculum generation is not individualized to the learner and dictates for the clinician to follow a linear progression across skills. This linear approach forces an unnatural progression across skills. For example, it forces the jump from motor to language to social skills abruptly without behavioral explanation of the transition or flow. This also proves to be a challenge when some skills require prerequisites across content areas. For example, plays simple ball games requires both motor skills (to manipulate the ball), language skills (tacting), and play skill (listing rules). As such, it requires multiple direct elements across content areas whereas it does not linearly extend from one skill or area.

Take Home Points

-

Instructional design will result in a web-like element-compound analysis instead of a linear progression across skills.

-

This allows for individual and logical flow across multiple curricular content areas to support learner success.

-

If a learner is not successful, evaluate the curriculum and its design.

Click here for Part II of The Importance of Instructional Design!

Unlocking Potential through CR Elements Clinical Program

CR Elements, our digital ABA curriculum covers a wide range of topics, ensuring that your clients receive a comprehensive and well-rounded learning experience. Want to learn how you can save time and enhance clinical care with CR Elements seamless integration with CR Essentials?

Dr. Kerri Milyko, BCBA-D, LBA(NV)

Dr. Kerri Milyko came upon behavior analysis as a student of Dr. Henry Pennypacker at the University of Florida. Upon his encouragement, she forged a path that led to the University of Nevada-Reno studying under Dr. Patrick Ghezzi and then, as an entrepreneur opening precision teaching clinics in Tampa and Reno. Dr. Kerri served at CentralReach as the Director of Clinical Programming in 2019. In this role, she and her team created a fully digital, integrated, evidence-based curriculum, CR Elements, to service the needs of neurodiverse learners. Before this role, she was Director of Research and Development of The Learning Consultants and Development and Outreach of Agile Learning Solutions (formerly Precision Teaching Learning Center). Dr. Kerri is also adjunct faculty at the University of West Florida where she created and taught their VCS, master's-level Instructional Design class. Her primary behavior analytic focus is on instructional design, humane and dignified practices, measurement, precision teaching, direct instruction, percentile schedules of reinforcement, behavioral education, and bettering products for clinicians.

Finally, Dr. Kerri is a prolific volunteer. In 2019, she was elected to serve 3 years on the Board of Directors for the Standard Celeration Society. In the same year, she was appointed by the governor of Nevada to serve on the first-ever Board of Applied Behavior Analysis to create ABA practice regulations for the licensure of state behavior analysts, where she served as Chair of the Board for 2019. Currently, she serves as a trustee for the Cambridge Center for Behavioral Studies, a member of the Professional Standards Committee for the California Association for Behavior Analysis, and serves as the Teaching Behavior Analysis Program Area Coordinator for the Association for Behavior Analysis, International. Kerri values quality time with her three children, her husband, and dear friends. She loves wine and butter, true crime podcasts, and a good sci-fi novel while tinkering in her backyard.

References

Department of Defense. (2019). The Department of Defense comprehensive autism care demonstration quarterly report to congress second quarter, fiscal year 2019. https://www.altteaching.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/TRICARE-Autism-Report.pdf?fbclid=IwAR2IoxFQDGTAIT3GI-sUiDLlCH7WchjHEapect9zTMvUCyI_sOmWp3wbZsg

Taylor, R. [CABA Consulting]. 2020, February 25. Adult services: Listen up EIBI peeps! By Dr. Rachel Taylor, at ILABA [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/s7bidyjGFaU